How to Break Art and Bend Gravity, Part 1.1

Side A: First Brush with Blood-and-Maggot Art

Side A: First Brush with Blood-and-Maggot Art

John Singer Sargent was a hell of an artist. He was the greatest portraitist in the world during the early 1900s, when he flattered lords in London and Paris with his exuberant brushwork. He died a wealthy man.

When I was fifteen, I wanted to paint like Sargent. A friend and I even tried. We reworked our own paintings obsessively in hopes we’d lay down a few brushstrokes as lively as his. Surely anyone I’d pass on the sidewalk would kill to paint as he did.

But when I studied fine art painting in college, I learned that some people had bizarre tastes in art and culture.

I decided this after getting to know a classmate, Marc, who loathed Sargent. He called him “more illustrator than artist,” which I guess meant Sargent's paintings were shallow and inconsequential. Marc urged me to check out a new artist, Damien Hirst. "He makes real art, and when you see his stuff you'll understand why Sargent isn't good.”

Marc's attack on Sargent ought to have bumped him off my would-save-from-drowning list. But Marc had intrigued me with his cultural literacy. See, he was the guy who, after painting class let out, would hang back with our professor and trade notes about contemporary artists. He dropped lines like, “I love how Twombly transcribes his own mental life so intimately. And he makes understated works while bombastic, over-the-top graphic art is trending!” Normal students don't talk that way—I didn't, and I'd shuffle past him without knowing any of the artists he went on about.

Six month later, I got to see the great Damien Hirst's work. It was near semester's end when I joined friends on a bus to the city. We were out for live standup and nightlife, and a friend mentioned that a Damien Hirst retrospective would open soon. That was Marc's guy! The one who put Sargent to shame!

My friends went back to campus, but I hung out two more days to catch the show's opening. I don’t know what I expected to see there. Murals? Certainly not a crowd gathered round a rotting cow’s head on the gallery floor.

The artist Hirst had flung it there, and he’d built a heavy 7-foot-tall glass case around it to lock in all the flies—there were so many! And they laid eggs in the late cow's gums and tearducts before they ascended into a bug zapper hanging overhead. Then, with sharp hisses, they dropped back to the floor. They bounced a little when they landed.

My friends went back to campus, but I hung out two more days to catch the show's opening. I don’t know what I expected to see there. Murals? Certainly not a crowd gathered round a rotting cow’s head on the gallery floor.

The artist Hirst had flung it there, and he’d built a heavy 7-foot-tall glass case around it to lock in all the flies—there were so many! And they laid eggs in the late cow's gums and tearducts before they ascended into a bug zapper hanging overhead. Then, with sharp hisses, they dropped back to the floor. They bounced a little when they landed.

If Prince Joffrey made art, it would look like this.

I stood close to the glass and noticed that guys elbow-to-elbow with me wore ascots and expensive shoes. They leaned at the glass, spellbound by the blood, maggots, and all the dead flies. And I wondered how they’d react to skillful paintings by John Singer Sargent. Would they yawn and wave them away as Marc had done? These assholes would probably mock Sargent for being more illustrator than artist too.

I made a move to the wine table, where a guy with a luxury watch to go with his forearm tattoos asked me what I thought of the show. I was trying to keep an open mind, I said, but this wasn’t the kind of art I usually consumed.

He explained that Hirst was the highest-paid artist living today. He stacked chips like Daddy Warbucks because he forced everyone to stare death in the face, and not only a cow's death. He'd also given a thousand flies the choice: to gorge themselves on cow cheek or to ride the lighting. Thirty-six inches separated these fates. Hirst probably grew up torturing chipmunks in the toolshed, but he had another side—he was a competent craftsman. He’d encased his carnival of dead animals in plate glass with clean, black-framed edges. At the far side of the glass case was a big white cube—as tall as a desk, and with one hole on each face like a Milton Bradley die.

Did Hirst want me to take death lightly? Did he want me to think on my own mortality? Did he want to rebel against talent and technique? Or maybe he wanted to push ugly in my face to wind me up.

I made a move to the wine table, where a guy with a luxury watch to go with his forearm tattoos asked me what I thought of the show. I was trying to keep an open mind, I said, but this wasn’t the kind of art I usually consumed.

He explained that Hirst was the highest-paid artist living today. He stacked chips like Daddy Warbucks because he forced everyone to stare death in the face, and not only a cow's death. He'd also given a thousand flies the choice: to gorge themselves on cow cheek or to ride the lighting. Thirty-six inches separated these fates. Hirst probably grew up torturing chipmunks in the toolshed, but he had another side—he was a competent craftsman. He’d encased his carnival of dead animals in plate glass with clean, black-framed edges. At the far side of the glass case was a big white cube—as tall as a desk, and with one hole on each face like a Milton Bradley die.

Did Hirst want me to take death lightly? Did he want me to think on my own mortality? Did he want to rebel against talent and technique? Or maybe he wanted to push ugly in my face to wind me up.

My friend with the luxury watch further explained that Hirst’s installation was one link in a long chain of blood-and-maggot art. Before Hirst, Andy Warhol had made silkscreen prints of gory car accidents and electric chairs. One electric chair would have disturbed us, but Warhol repeated the images like a pattern—like wallpaper. And with it, he covered 7-foot canvases that diminished the electric chair's shock value. His fans called his work a metaphor for how news stations numb us all to death and suffering by showing us too many grisly stories.

He walked me through all the reasons why Damien Hirst’s art should captivate me. And I appreciated the patience he'd lent me, but I still couldn’t muster any admiration for blood-and-maggot art. More, I couldn't find common ground with its enthusiasts who'd constructed a clown-world where down was up and ugliness was beauty. I didn't know the first thing about what made contemporary art buyers tick, so how could I thrive as a fine art professional? Rarely had I felt more like an outsider than I did here tonight.

Side B: Eye of the Beholder

I met another outsider that night. She was an ethologist, which meant she studied animal behavior. She was older—she'd graduated and was out on her own.

For my own amusement, I tried convincing her I was here to service the bug zapper. She played along for a minute, until she finally wanted to know, “What do you really do then?”

“Art school.”

“Hmm. You know this guy's story?” she asked and pointed to Hirst’s glass case of wonders. "The artist, not the cow."

“Never seen his work before tonight, not even in pictures," I said. "I came because a buddy recommended I take in highbrow art for a change.”

“Opposed to?” she asked.

“John Singer Sargent, the old masters, illustrators. Anyone with technical skill.”

“Sargent's a good one,” she said and smiled. I liked her. She said, “So you took your friend's advice and came to a Hirst show. I wonder if you're glad you came.”

I didn't hold back: I said the rotting cow’s head belonged on stage at a Marilyn Manson concert.

She raised an eyebrow. “That's disgusting. He does that, really?”

I confessed I knew next to nothing about Manson, but maybe he and Hirst had common interests.

“No, you can't compare Hirst and Manson. Come on, Hirst's a brilliant artist, and he's in a different orbit than the rest of the contemporary artists."

I shrugged.

"Have you been to many of these gallery openings?"

"None," I said.

"I've been to a few dozen, and may I share my impressions? At least half the paintings and sculptures at these shows are impenetrable. Like I can't make sense of what I'm looking at. I've seen nests made out of human hair, and that's not even the weirdest. The established art critics who try to vouch for those stupid works sound like they’re speaking in tongues.”

"I see."

"I see."

“So you've got one half of contemporary art that just doesn't make much sense, and then the other half does make sense, but it's preachy. You know what I mean by preachy . . . I'm picturing all those artists who browbeat you with shallow truisms like ‘Consumerism is bad’ or ‘Shaming women for having periods is bad’ or ‘Corporate greed—’”

“Wait, isn't consumerism bad?” I asked.

“I mean if you thought it wasn't, would an art installation change your mind? Would a stack of handbags, painted gold, with a silhouette of a businessman looming behind it change your mind? I doubt an art installation would ever move the needle for your consumerist behavior."

"Probably wouldn't."

"And let's pretend some artist collected and stacked up a pile of bloody tampons. Would this convince you not to period-shame her? However," and here she held my arm and spoke carefully: "when I walk into a gallery, I offer an artist my unflinching attention. I hope she'll teach me something new or show me something special—something more erudite and nuanced than ‘Consumerism is bad.’ Yeah?”

“That's fair," I said humbly, recognizing that I knew so much less than she did about contemporary artists.

"But Hirst is one of a very few artists who can change hearts and minds," she was saying, "because his work's accessible."

"It is?"

"Oh yeah!" she said, "Look, look, we don't have to read his manifesto to get that his work's about life and death. And once you're drawn in, you'll start to weigh the life of a single cow against the lives of five thousand flies. And you'll consider how much control the flies really have over their fates. You'll wonder whether your own freedom is a deception. Bam! This . . . ,” and she was gesturing aggressively at the glass, “is equal parts terrifying and exhilarating! Do you know how fast my heart beat when I first saw this? Seriously, what a privilege! What a privilege to be a part of this.”

A privilege? I said my heart was racing when I walked in here too, but a visit to a morgue would’ve given me the same rush. Who judges art by its shock value anyway? Because by that metric, wouldn’t the greatest art of all be a row of amputated human heads? Or looping clips of gore? Or why not real blood and phlem that dribbles all down your neck and back as you carry on about the artist's brilliance? No, body horror didn’t belong in a gallery. Hirst didn’t deserve praise, and he definitely didn’t deserve to outshine Degas, Wyeth, and real, honest artists who'd mastered their craft.

I caught my breath. Had I been unfair? Maybe I owed Hirst credit for inspiring Marc when Sargent couldn't. Maybe Hirst wasn't stealing market share from Sargent at all, and I needed to chill.

I apologized to the ethologist for trashing the art she loved. She'd spoken kindly of Sargent after all.

She shook her head. "You're not the first one to rage against contemporary art, but there's still hope."

"Yeah?"

"You'll acclimate to Hirst as you see more."

I chewed on that thought: would blood-and-maggot art really grow on me if I saw more of these shows? Because if so, that meant I liked certain foods, art styles, and music because I'd been repeatedly exposed. In which case I hadn't chosen Team Sargent, but my tastes had been chosen for me, curated by my parents and peers.

One art history lecturer at my school was known to slip slides of random paintings into his lectures. When they appeared he'd say, "We won't talk about this painting today." Then at semester's end, he'd ask students to rate how much they liked a series of paintings—mostly ones they'd never seen but also a few plants he'd shown previously and without explanation. Miraculously, they reported liking paintings better when they'd been merely exposed.

I liked Sargent because I'd been merely exposed to his style.

The ethologist was saying, “When I taught animal behavior as a grad assistant, most of my students insisted that their childhoods determined whatever food, art, and music they liked. But to my surprise, the same students would turn around and say 'beauty's in the eye of the beholder.' That baffled me—to say 'beauty's in the eye of the beholder' implies tastes aren't determined by anything—that they're random! Yeah? It's like everyone draws from a deck of cards at birth, figuratively speaking, and if you draw 5 of clubs you're destined to like gala apples and reggaeton."

"That seems to be the case, though. Some people like galas and some don't." I said.

"You're not wrong, I like honeycrisps better than galas. But that not a random preference. Random preferences would mean half the population chooses rotting apples over ripe ones. And half the population chooses grey-brown, wilted flowers over fresh blooms. Supply your own examples here. Tastes would be all over the place if they were random, if beauty were in the eye of the beholder. Heh, Shop 'n' Save in Eyeofthebeholderland would have to stock its produce sections with apple tree bark, apple tree leaves, unripe apples, and rotting apples, and they'd all sell as well as ripe apples."

[insert illustration: the produce section in eyeofthebeholderland]

"Stay with me," she said. "As humans, we're all grossed out by rotting fruit because of either nature or nurture, right? Do we like ripe apples better than rotten ones because our parents and older siblings nudged us that way? Or, did the instincts we were born with prime us to like sweet, juicy things?"

"So which is it?" I asked.

"Well, to find out, we want to isolate newborns in a lab and restrict their interactions with parents. Watch their natural, unlearned tastes emerge—either for fresh or rotten apples. But ethics boards would nix that experiment, so the next best thing we can do is observe kids from faraway cultures. They haven't been compromised by Western media. So if we do this, what do you think we find?"

I didn't know that either.

"Tribes from isolated pockets of the Amazon still like blooming flowers and fresh fruit and meat. And they all like Beyonce's singing voice better than yours, no offense." She went on, "So yeah, we can pick out a bunch of universal, pan-cultural preferences for certain kinds of music, dance, and food. Human nature seems to drive our tastes after all. Granted environment plays some part too, obviously, as does randomness. But don't discount the role of the hardware we're born with," and she tapped her forehead with two fingers, "in deciding what we like."

"Do we instinctively find any kinds of visual art beautiful?” I asked, because I doubted there could be any common ground between Team Hirst and Team Sargent.

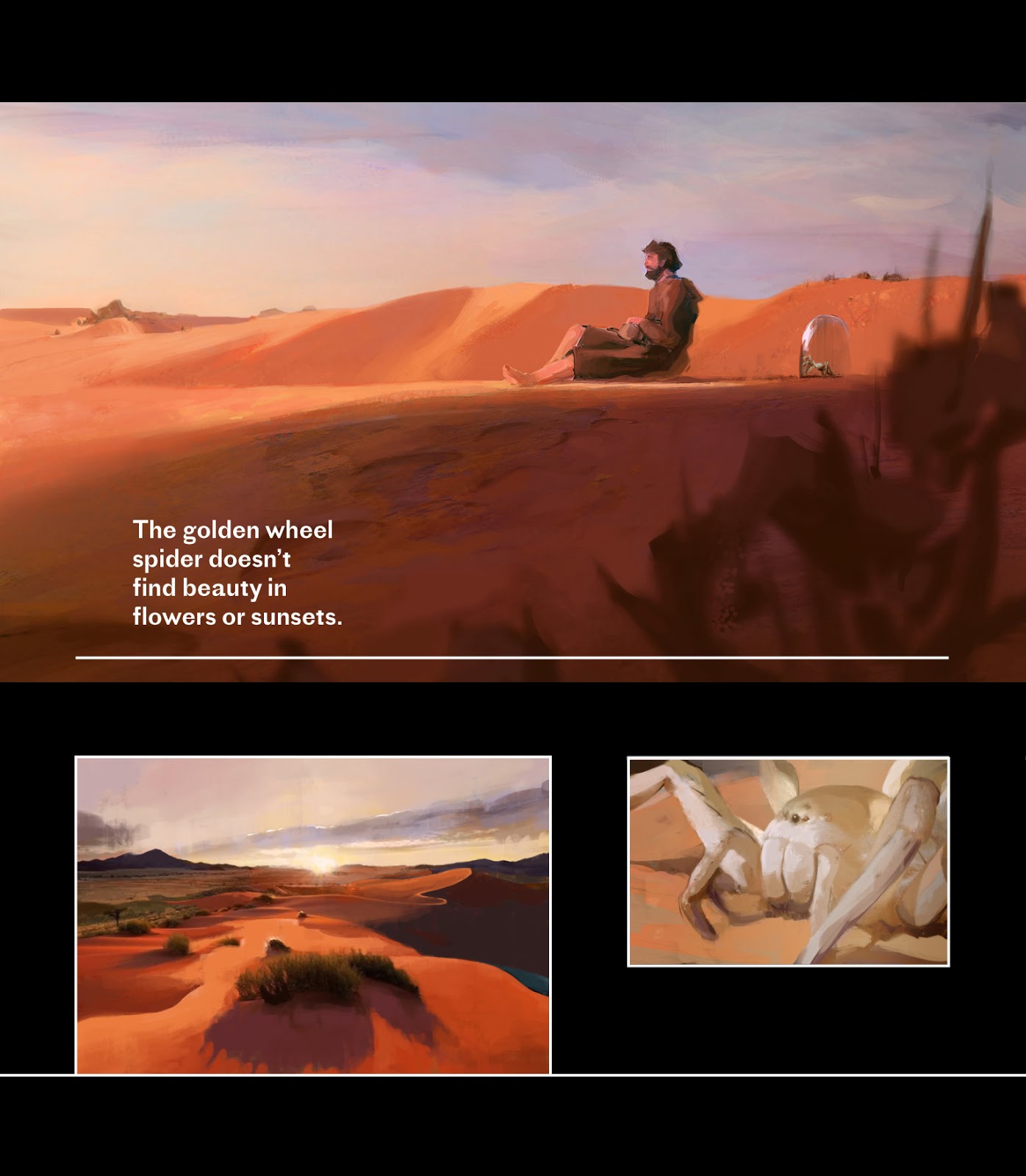

She thought for a second before saying, “Best candidates are chevrons and checkers, florals, and some other botanical patterns. We're probably wired to like certain color schemes too, some arrangements of shapes. Yeah, and definitely subjects like rolling hills with fluffy clouds, like those above your headboard at a bed and breakfast. And flowers . . .”

[illustration: best candidates for universally appealing visual art]

“Hang on," I said, "because people in this room would scoff at landscape paintings or floral patterns. They're into blood-and-maggot art.”

“Doesn't make sense, does it? Most consumers of contemporary art call landscape paintings with fluffy clouds lowbrow and kitschy. They roll their eyes at Sargent. But what if thinking a painting's unfashionable is different than thinking it's ugly? Maybe human conceptions of beauty didn't change the day Picasso, Pollock, or Hirst started making art.”

I allowed that Marc probably didn't decorate his apartment with dismembered animal parts. He and other Hirst fans confined their fascination with blood and maggots to a narrow context. But then, didn't tribes in New Guinea and Nigeria also have totally different ideas of beauty compared to Americans?

"You mean because of their ceremonial masks?" she asked with a smile. "You think New Guinean craftsman intend their masks to be exemplars of beauty? Be careful. That's like saying the Parisians who built Notre Dame found gargoyles beautiful. In reality, gargoyles tell us nothing about what gothic Parisians thought beautiful, and New Guinean masks tell us nothing about what New Guineans think beautiful. I'd guess that ceremonial masks are meant to look unsettling."

[illustration: the existence of plague doctor masks tell us nothing about what black-death-era europeans considered beautiful]

She had a point. Still, I hated the idea of tying my tastes in art to human nature. All the cool kids thought beauty was in the eye of the beholder. That seemed to be the side most aligned with progress and equity. No wonder her students leaned that way.

Still I was hung up on something she'd said before, so I asked, "What did you mean when you told me Sargent's unfashionable and kitschy?"

She said that among the art elite, skill had become a bad word. That's why I'd be hard pressed to find high-end galleries that sold naturalistic paintings, the kind I made.

Inconsequential illustrators were out, blood-and-maggot artists were in, and I was a dinosaur. This was the first time I'd given real thought to my path after college.

I half-joked that I should try my hand at blood-and-maggot art, since it was trending.

But she shook her head and said, "No, that style's inauthentic to your tastes and personality. It won't work."

I wanted to protest, but she was right. There was no universe in which could I speak the language of Team Hirst well enough to sell hundred-thousand-dollar artworks to that crowd. I was an outsider.

She said, "You'll stick with making art you feel good about. What else can you do?"

I said I could learn actuarial science or petroleum engineering, some useful trade.

"Come on," she said. "Time for a drink."