How to Break Art and Bend Gravity, Part 1.3

Side A: The Unfashionable Majority

While waiting in line at the bus station, I paid more attention than usual to the other passengers. I was trying to guess who’d align with Sargent or Hirst. Team Sargent would attract the high-conscientiousness and mid- to low-openness commuters. That meant violinists, actuaries, chemists, and other guys who dressed like Jon Arbuckle. Meanwhile, Team Hirst would attract the competitively eccentric creatives, plus a few highbrow socialites whose parents and peers had systematically desensitized them to blood-and-maggot art.

Side A: The Unfashionable Majority

While waiting in line at the bus station, I paid more attention than usual to the other passengers. I was trying to guess who’d align with Sargent or Hirst. Team Sargent would attract the high-conscientiousness and mid- to low-openness commuters. That meant violinists, actuaries, chemists, and other guys who dressed like Jon Arbuckle. Meanwhile, Team Hirst would attract the competitively eccentric creatives, plus a few highbrow socialites whose parents and peers had systematically desensitized them to blood-and-maggot art.

A young latina lady in line ahead of me wore combat boots and a dozen bracelets on each wrist. I thought she'd be a fine candidate for Team Hirst if the guys from the art show ever came out recruiting. But the fifteen others in line belonged to Team Sargent. And here was another important insight: Team Hirst was a tiny tribe. They were the early adopters, the first movers. Maybe they'd even sway the majority to join them someday.

Or maybe not. I could see Team Hirst remaining on the fringes the same way kids with tarantulas would forever stay an insignificant subset of pet owners. (How many lifetimes would we have to wait for the hordes of irish setters owners to abandon their dogs in favor of pet spiders?) Team Sargent might not attract the trendy innovators, not in the fine art domain, but they were the middlebrow majority.

Still, the problem with Team Sargent was that they built a 600-year backlog of more phenomenal art than they could ever sift through, so they could ignore future generations of art makers. I'd need to outpaint Rembrandt and Turner to make a splash.

By contrast, Marc wouldn't have to be a one-in-fifty-million virtuoso to win attention as a blood-and-maggot artist. All he had to do was to show his fans the next clever idea. That was no cakewalk either, but it was an order of magnitude easier than besting Rembrandt or Turner.

That's all to say I decided it wise to look for opportunities outside the "fine artist" profession. And soon the ethologist would give me my first lead.

Side B: The Spider’s Tale

My bus pulled out at 10:15 PM. Soon, the city lights were behind me, and I was barreling down a long, straight corridor of highway. It sank between a grassy embankment on either side, upon which grew thick trees that loomed over me.

My mind wandered.

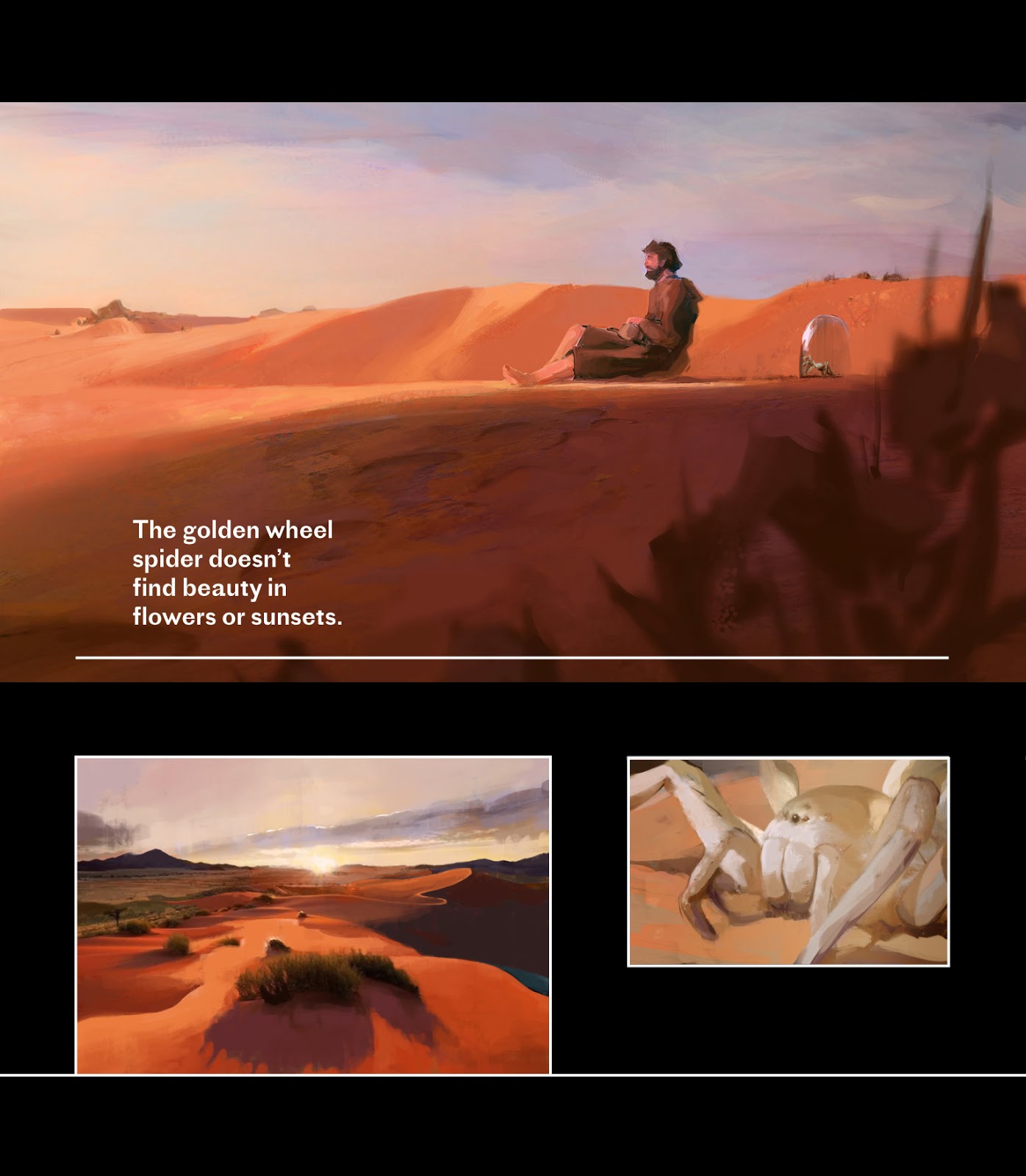

I stared out the window and imagined the embankments shedding their grass and then climbing a hundred feet higher. The cars were gone, and even the highway disappeared beneath hard-packed sand. That's when the bus rolled to a stop. The passengers weren't there any more.

I was sitting alone when the sand began to invade the bus’s aisle. It came in waves, rolling past me and swallowing the floor. Layer after layer of sand kept piling on until it was up to my knees. I had to lean forward use the seat in front of me like a fulcrum to yank my feet free. Then I climbed out the bus's ceiling exit and started up the nearest dune. It was still a silhouette against the night sky.

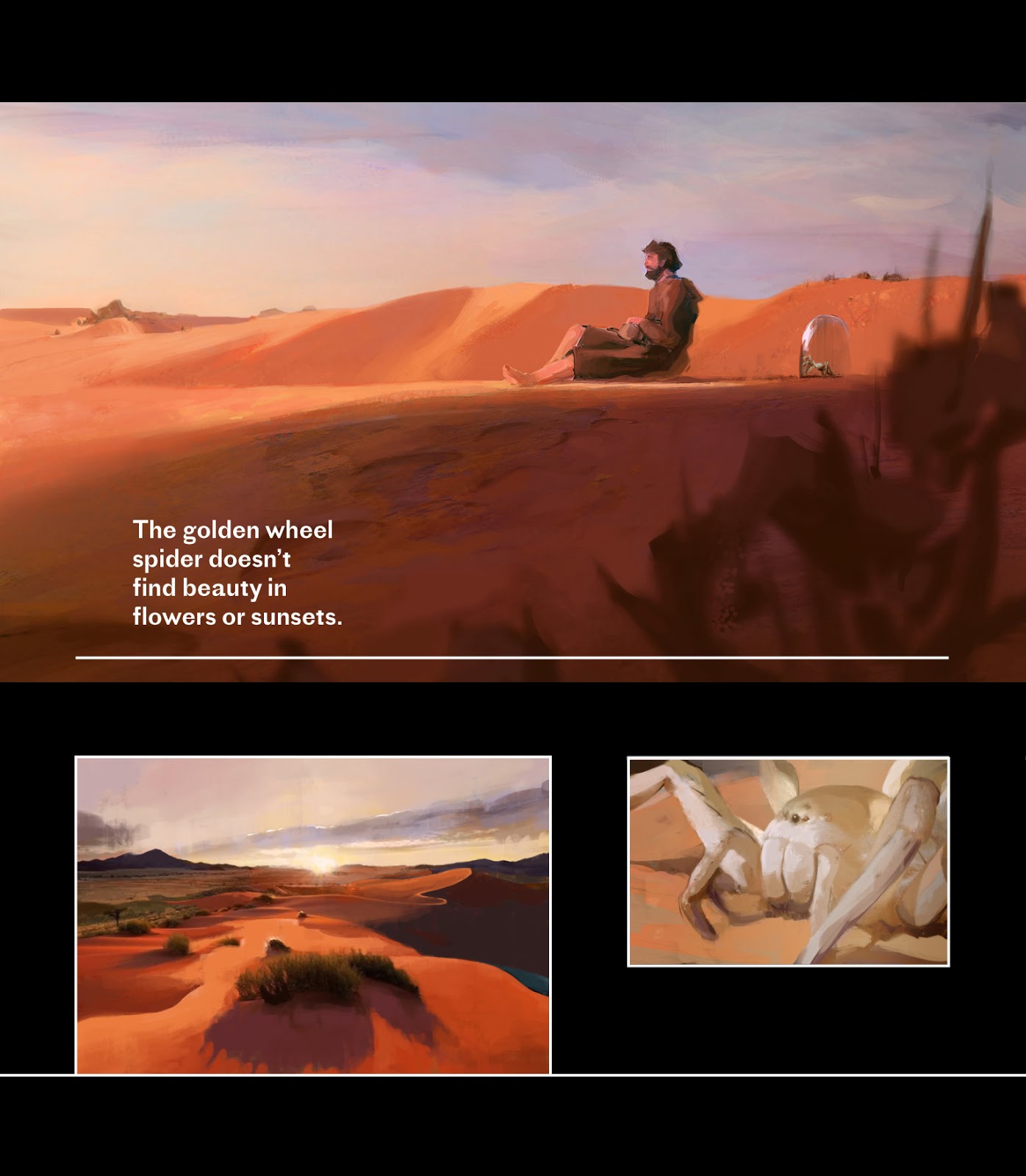

The sun broke the horizon as I reached the summit. It shone on the sand ahead of me, revealing a little glass dome—the kind a baker uses to cover cakes. I approached and saw that underneath the dome was the same golden wheel spider the ethologist had described. He stood motionless, as small as my palm and beige to match the sand.

I knelt beside him and started to lift the glass off him. He spoke, or rather I heard a voice I imagined to be his, though he never moved. The voice said: “Leave the cover where it is, please.”

Suppose you could converse with a golden wheel spider. What would you ask him? What would he ask you?

Earlier tonight, the ethologist had told me a bit about this spider’s habits. I knew, for instance, that he didn’t build webs because they were useless on the dunes. I knew he dug a burrow and tucked himself underground from sunrise to sunset. And I knew that at night, he crawled out to hunt for bugs.

“I’m not one to lounge in the open like this,” the voice said, “not when the sun’s up. So forgive me if I seem edgy.”

The sand would be searing hot to the touch in a couple hours, but it was cool now. We had a spectacular view across the sandy expanse, which were turning the color of rust in the sunlight. I told him I was privileged to enjoy such a beautiful vista.

“That’s interesting,” he said.

“What?” I asked.

“I’m puzzled by what you call beautiful. Sunsets and expansive views with big skies? I assure you that if we auctioned off apartments to my relatives, the windowless basement units would fetch the highest prices. You can keep your penthouses with big windows and balconies looking out over the beach.”

Really?”

“We’re burrowers,” he said. “We avoid sunlight and open spaces the best we can.”

I thought living in a cramped burrow and barely able to move would take its toll on anyone. Maybe some sunlight and fresh air would be good for him if he’d only let me remove the glass cover.

“And then I want you to help me understand a couple strange habits for which humans are known . . .”

I tried to guess which habits baffled him. Maybe he couldn’t wrap his head around how men bring themselves to torture each other, or why we consume books, songs, and films that make us sad. These quirks must seem queer to a non-human.

“It seems strange,” he said, “that you plant gardens of inedible crops, like roses. And that you wear impractical clothes, like white silk shirts that can’t sustain the slightest bit of wear or soiling. And you squander so many hours and calories building 60,000-word vocabularies, when an 850-word vocabulary would let you express yourself precisely and effectively. Oh, I’ve even heard that you build massive fountains that you never drink from. Help me out.”

He was pushy, and I didn’t know how to field his questions. So I deferred to the ethologist’s guiding principle: that everything we observe in nature has a backstory. I said, “You must understand that humankind climbed to the pinnacle of animal intelligence. Big vocabularies came bundled with our big brains, like a byproduct. If spiders had big brains, they’d plant rose gardens and wear ornate costumes too.”

“That doesn’t make any sense. No, see, if you were smart, you’d dress in the most durable materials available. You’d probably wear navy to hide stains. Or better yet, you wouldn’t fuss about stains, since a stained shirt and a clean shirt keep you warm all the same. And you’d plant edible crops, but never flowers, which have no use.”

Again with the flowers. I told him rose gardens look and smell lovely.

“Why?”

I stared at him.

“You don’t know. That’s alright, but remember that some of the animals with the most powerful noses are indifferent to the smell of flowers, which means flowers aren’t objectively nice-smelling or pretty-looking—they’re only so in your brain.”

I thought of how few young people filled their homes with floral patterns. The trend had fallen out of favor since my grandparents’ time. I decided I’d have to ask the ethologist next time I saw her how we came to like the look and smell of flowers. My question for the spider was: “What looks beautiful to you?”

“Actually, nothing,” he said, and I thought I now understood why he spoke so abrasively. “I mean nothing looks beautiful to me. I only read beauty in what I can feel or smell. So then beauty to me is feeling the footsteps of a she-spider vibrating through the sand, especially when I can tell she has strong legs for digging burrows. I’ll trek 100 meters just to feel her lovely steps, and I’m smitten by the feeling. On top of that, her scent puts me in a trance.”

I said he was romantic.

“How could anyone feel the steps of a she-spider and not recognize her exhilarating beauty?”

It was my turn to challenge him. I said that even if I had specially calibrated instruments to detect spider footsteps, I wouldn’t call them beautiful.

“No, I supposed you wouldn’t. And by the same logic, if I had ears and could listen to Beyoncé, her voice wouldn’t please me any more than radio static or fingernails across a chalkboard. Human music is for humans alone. ”

“Your use of the term ‘human music’ casts a pretty wide net.”

“Yes and no” he said, “Listen, if you play for me jazz, electronica, traditional Mayan music, and Javanese gamelan, I can distinguish between these genres probably 80% of the time—I mean, just by feeling the speed of the vibrations, the tempos and beat structures, I can pick up clear differences. But then, if you play me jazz, whale songs, frog songs, and cicada songs, the difference is an order of magnitude greater. Even bird songs could never be mistaken for human music because they’re missing the core melodic and rhythmic structure you’d find in your musical genres. That underlying structure is what attracts you.”

“I guess so,” I said, while trying to think of evidence that would dispute his claim. Here was something: I bet he’d never heard of atonal compositions like those written by the experimental composer Arnold Schoenberg. They had neither rhythms nor melodies, and they sounded like someone had randomly patched them together measures from other symphonies to create a messy jumble of notes. What structural similarity could be found between Mozart and Schoenberg?

“Human tastes are phenomenally pliable,” the spider said, “but that doesn’t mean you don’t have innate pleasure buttons. Let’s say you gathered 10 representatives from every human culture on the planet, from Amazon tribespeople to New Guineans. And you asked all the participants whether they liked Mozart or Schoenberg. What would happen?”

“A few would vote for Schoenberg,” I said.

“Right, and yet the vast majority would vote for Mozart. Now if beauty were in the eye of the beholder, you’d expect preferences to be half and half. That’s not what we’d see, though. The dramatic skew to Mozart, which we see even among those who never heard Western radio, suggests that humans are probably wired to like a melody with a beat. Someone could probably define pan-cultural music tastes in more detail, but I won’t try.”

“How do you explain the outliers that like Schoenberg better than Mozart?” I asked.

“Your environment can override your genes in fringe cases. That’s why almost every human is grossed out by rotting meat, save for a few Icelanders and Swedes who eat spoiled shark and fish. And almost every human is terrified of spiders, save for a few outliers who adopt them as pets. So in all these cases, environmental pressures can coax people away from their instinctive aversion to atonal music, bad meat, or spiders. ”

I was scared of spiders. Not that I wanted to feel afraid, but that response grabbed hold of me despite my best efforts. I didn’t say anything, but I wondered if he noticed me stiffen up when I’d first approached him.

The spider was saying, “We spiders aren’t objectively scary, but you evolved to fear us. Do you know why?”

I guessed that a long time ago, spider bites were a frequent cause of death. Arachnophobes took steps to protect themselves, like flicking spiders off their calves. Thus, arachnophobes out-survived people indifferent to spiders, which is why I'm descended from arachnophobes.

“You get that each of your pleasure buttons—your attraction to flowers, fountains, expansive views, and rhythmic music—also somehow helped your ancestors survive and make babies.”

I asked whether our pleasure buttons might be accidental byproducts of our big brains.

“Probably not,” he said. “You like things that were good for your ancestors. Listen, I've got instinctive likes and dislikes same as you, and they all make sense in terms of evolution. Like when I lie underground in a dark, cramped burrow, and when I feel the sand pressing against my belly, I feel nirvana.”

You tell him a dark, cramped burrow would make you feel panicked like you’re about to suffocate.

“Why do you think my brain links pleasure to burrowing?” he asked.

“Because,” I said, “your ancestors needed to protect themselves from the scorching sun to retain water.”

“That’s part of it, and they also had to stay hidden from predatory wasps. So a spider that walked in the daylight wouldn’t make it. The burrowers were the ones who kept out of trouble long enough to continue the golden wheel spider bloodline.”

I stood up. The morning was getting hot and I didn’t want the spider to dehydrate, so I thanked him for his wisdom. I also told him the sunrise over the dunes was gorgeous. What a treat!

“Would you lift the cover before you go?” he said. “I set up our conversation so you’d feel comfortable next to a spider.”

As soon as I did, he shot out of sight. Then I was back on the bus and moving again.

The sun broke the horizon as I reached the summit. It shone on the sand ahead of me, revealing a little glass dome—the kind a baker uses to cover cakes. I approached and saw that underneath the dome was the same golden wheel spider the ethologist had described. He stood motionless, as small as my palm and beige to match the sand.

I knelt beside him and started to lift the glass off him. He spoke, or rather I heard a voice I imagined to be his, though he never moved. The voice said: “Leave the cover where it is, please.”

Suppose you could converse with a golden wheel spider. What would you ask him? What would he ask you?

Earlier tonight, the ethologist had told me a bit about this spider’s habits. I knew, for instance, that he didn’t build webs because they were useless on the dunes. I knew he dug a burrow and tucked himself underground from sunrise to sunset. And I knew that at night, he crawled out to hunt for bugs.

“I’m not one to lounge in the open like this,” the voice said, “not when the sun’s up. So forgive me if I seem edgy.”

The sand would be searing hot to the touch in a couple hours, but it was cool now. We had a spectacular view across the sandy expanse, which were turning the color of rust in the sunlight. I told him I was privileged to enjoy such a beautiful vista.

“That’s interesting,” he said.

“What?” I asked.

“I’m puzzled by what you call beautiful. Sunsets and expansive views with big skies? I assure you that if we auctioned off apartments to my relatives, the windowless basement units would fetch the highest prices. You can keep your penthouses with big windows and balconies looking out over the beach.”

Really?”

“We’re burrowers,” he said. “We avoid sunlight and open spaces the best we can.”

I thought living in a cramped burrow and barely able to move would take its toll on anyone. Maybe some sunlight and fresh air would be good for him if he’d only let me remove the glass cover.

“And then I want you to help me understand a couple strange habits for which humans are known . . .”

I tried to guess which habits baffled him. Maybe he couldn’t wrap his head around how men bring themselves to torture each other, or why we consume books, songs, and films that make us sad. These quirks must seem queer to a non-human.

“It seems strange,” he said, “that you plant gardens of inedible crops, like roses. And that you wear impractical clothes, like white silk shirts that can’t sustain the slightest bit of wear or soiling. And you squander so many hours and calories building 60,000-word vocabularies, when an 850-word vocabulary would let you express yourself precisely and effectively. Oh, I’ve even heard that you build massive fountains that you never drink from. Help me out.”

He was pushy, and I didn’t know how to field his questions. So I deferred to the ethologist’s guiding principle: that everything we observe in nature has a backstory. I said, “You must understand that humankind climbed to the pinnacle of animal intelligence. Big vocabularies came bundled with our big brains, like a byproduct. If spiders had big brains, they’d plant rose gardens and wear ornate costumes too.”

“That doesn’t make any sense. No, see, if you were smart, you’d dress in the most durable materials available. You’d probably wear navy to hide stains. Or better yet, you wouldn’t fuss about stains, since a stained shirt and a clean shirt keep you warm all the same. And you’d plant edible crops, but never flowers, which have no use.”

Again with the flowers. I told him rose gardens look and smell lovely.

“Why?”

I stared at him.

“You don’t know. That’s alright, but remember that some of the animals with the most powerful noses are indifferent to the smell of flowers, which means flowers aren’t objectively nice-smelling or pretty-looking—they’re only so in your brain.”

I thought of how few young people filled their homes with floral patterns. The trend had fallen out of favor since my grandparents’ time. I decided I’d have to ask the ethologist next time I saw her how we came to like the look and smell of flowers. My question for the spider was: “What looks beautiful to you?”

“Actually, nothing,” he said, and I thought I now understood why he spoke so abrasively. “I mean nothing looks beautiful to me. I only read beauty in what I can feel or smell. So then beauty to me is feeling the footsteps of a she-spider vibrating through the sand, especially when I can tell she has strong legs for digging burrows. I’ll trek 100 meters just to feel her lovely steps, and I’m smitten by the feeling. On top of that, her scent puts me in a trance.”

I said he was romantic.

“How could anyone feel the steps of a she-spider and not recognize her exhilarating beauty?”

It was my turn to challenge him. I said that even if I had specially calibrated instruments to detect spider footsteps, I wouldn’t call them beautiful.

“No, I supposed you wouldn’t. And by the same logic, if I had ears and could listen to Beyoncé, her voice wouldn’t please me any more than radio static or fingernails across a chalkboard. Human music is for humans alone. ”

“Your use of the term ‘human music’ casts a pretty wide net.”

“Yes and no” he said, “Listen, if you play for me jazz, electronica, traditional Mayan music, and Javanese gamelan, I can distinguish between these genres probably 80% of the time—I mean, just by feeling the speed of the vibrations, the tempos and beat structures, I can pick up clear differences. But then, if you play me jazz, whale songs, frog songs, and cicada songs, the difference is an order of magnitude greater. Even bird songs could never be mistaken for human music because they’re missing the core melodic and rhythmic structure you’d find in your musical genres. That underlying structure is what attracts you.”

“I guess so,” I said, while trying to think of evidence that would dispute his claim. Here was something: I bet he’d never heard of atonal compositions like those written by the experimental composer Arnold Schoenberg. They had neither rhythms nor melodies, and they sounded like someone had randomly patched them together measures from other symphonies to create a messy jumble of notes. What structural similarity could be found between Mozart and Schoenberg?

“Human tastes are phenomenally pliable,” the spider said, “but that doesn’t mean you don’t have innate pleasure buttons. Let’s say you gathered 10 representatives from every human culture on the planet, from Amazon tribespeople to New Guineans. And you asked all the participants whether they liked Mozart or Schoenberg. What would happen?”

“A few would vote for Schoenberg,” I said.

“Right, and yet the vast majority would vote for Mozart. Now if beauty were in the eye of the beholder, you’d expect preferences to be half and half. That’s not what we’d see, though. The dramatic skew to Mozart, which we see even among those who never heard Western radio, suggests that humans are probably wired to like a melody with a beat. Someone could probably define pan-cultural music tastes in more detail, but I won’t try.”

“How do you explain the outliers that like Schoenberg better than Mozart?” I asked.

“Your environment can override your genes in fringe cases. That’s why almost every human is grossed out by rotting meat, save for a few Icelanders and Swedes who eat spoiled shark and fish. And almost every human is terrified of spiders, save for a few outliers who adopt them as pets. So in all these cases, environmental pressures can coax people away from their instinctive aversion to atonal music, bad meat, or spiders. ”

I was scared of spiders. Not that I wanted to feel afraid, but that response grabbed hold of me despite my best efforts. I didn’t say anything, but I wondered if he noticed me stiffen up when I’d first approached him.

The spider was saying, “We spiders aren’t objectively scary, but you evolved to fear us. Do you know why?”

I guessed that a long time ago, spider bites were a frequent cause of death. Arachnophobes took steps to protect themselves, like flicking spiders off their calves. Thus, arachnophobes out-survived people indifferent to spiders, which is why I'm descended from arachnophobes.

“You get that each of your pleasure buttons—your attraction to flowers, fountains, expansive views, and rhythmic music—also somehow helped your ancestors survive and make babies.”

I asked whether our pleasure buttons might be accidental byproducts of our big brains.

“Probably not,” he said. “You like things that were good for your ancestors. Listen, I've got instinctive likes and dislikes same as you, and they all make sense in terms of evolution. Like when I lie underground in a dark, cramped burrow, and when I feel the sand pressing against my belly, I feel nirvana.”

You tell him a dark, cramped burrow would make you feel panicked like you’re about to suffocate.

“Why do you think my brain links pleasure to burrowing?” he asked.

“Because,” I said, “your ancestors needed to protect themselves from the scorching sun to retain water.”

“That’s part of it, and they also had to stay hidden from predatory wasps. So a spider that walked in the daylight wouldn’t make it. The burrowers were the ones who kept out of trouble long enough to continue the golden wheel spider bloodline.”

I stood up. The morning was getting hot and I didn’t want the spider to dehydrate, so I thanked him for his wisdom. I also told him the sunrise over the dunes was gorgeous. What a treat!

“Would you lift the cover before you go?” he said. “I set up our conversation so you’d feel comfortable next to a spider.”

As soon as I did, he shot out of sight. Then I was back on the bus and moving again.

No comments:

Post a Comment